In search of the missing signals

06 Sep 2017TLDR; An overview of current trends for feature learning in the unsupervised way: regress to random targets for manifold learning, exploit causality to characterize visual features, and in reinforcement learning, augment the objective with auxiliary control tasks and pre-train by self-play. There is so much to learn from unlabeled data and it seems that we have only skimmed the surface of it by only using labels.

What’s happening in the space of unsupervised learning in 2017? In this post I will give an overview of recent work, from a very biased, personal pick.

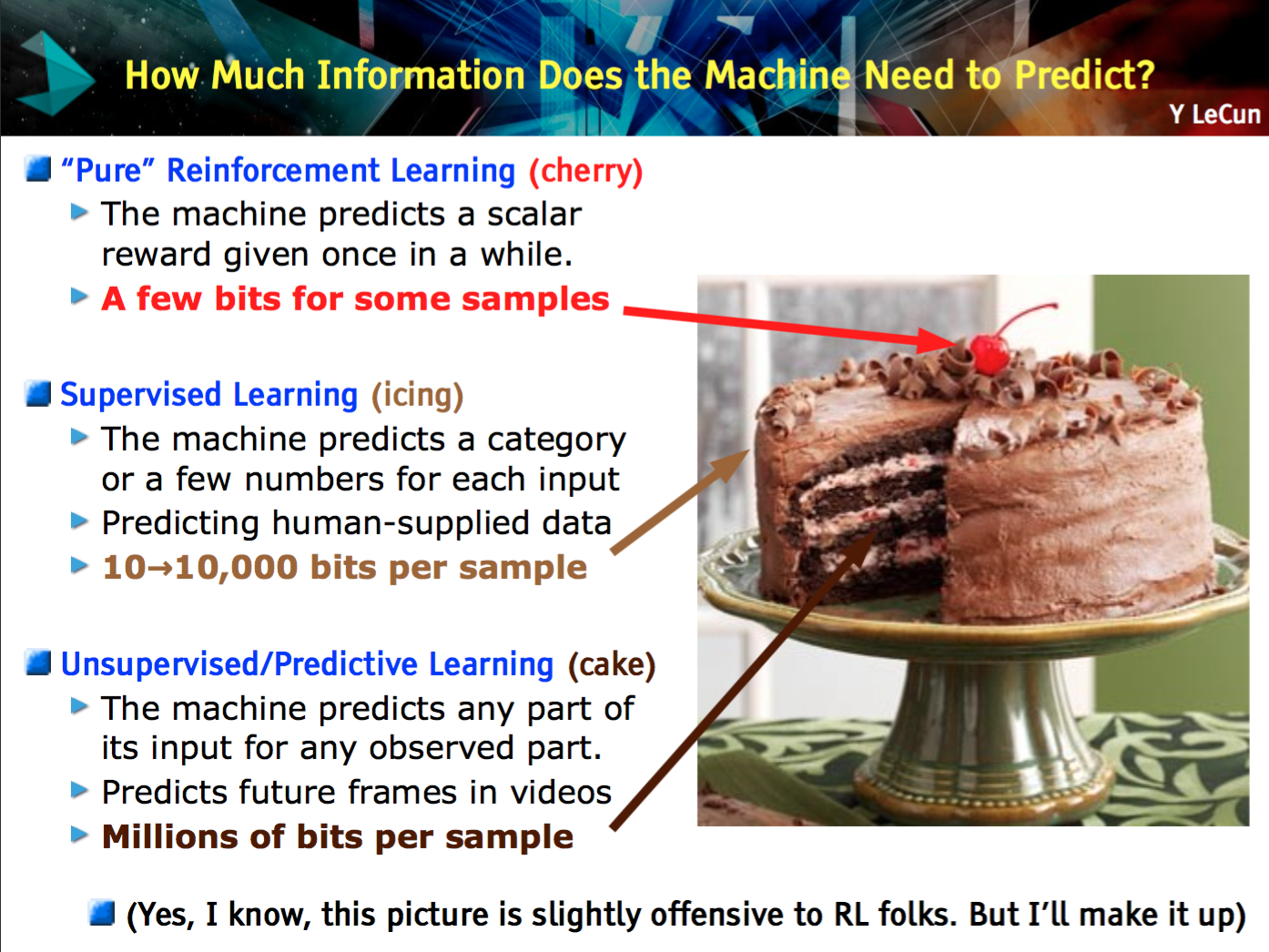

Unsupervised learning is a long lasting challenge in machine learning, perceived as a key ingredient for artificial intelligence — paraphrasing Yann LeCun. There is so much information in unlabeled data and we are not using it at the full extent, while it seems plausible that the human brain is designed to do so without supervision for most of its learning time. Or, in a picture, here you have the now famous LeCake:

The fact is, by training machines with many labels, they have a somewhat easier time with respect to how we — animals — may learn. Think about: finding intrinsic regularities; being surprised when those natural patterns are broken and therefore investigate their causes; acting by curiosity; training by playing. Neither of those require explicit supervision about what’s good or bad, in principle. Yes, this is a somewhat arbitrary list, but I made it up to roughly connect with the ideas loosely inspiring the papers I have selected for this post.

The unifying idea here below is finding self supervision in improbable, previously unexplored places of the data. Where should we look for signals when there is no label? Or, how to learn features without any explicit supervision?

Unsupervised learning by predicting the noise

[Bojanowski & Joulin ICML17]

A striking answer is given in here and that is: from noise.

I rank this paper among the very top ones at ICML this year. The idea goes as follows.

Sample uniformly random vectors from a hypersphere, in a number that is of the order of the data

points. Those are going to be the surrogates for the regression targets. In fact, learning

amounts to match images to random vectors, by learning visual features in a deep convolutional net,

via the minimization of a loss for supervised learning.

In particular, the training procedure alternate between gradient descent over the network parameters and a re-assignment of pseudo-targets to different images, again in order to minimize the loss function. Here the result on visual features from ImageNet; they are both results of training an AlexNet on ImageNet, on the left with the targets, on the right with proposed unsupervised method.

This approach appears to be state of the art in the cases of transfer learning explored in the paper. But why should it work at all? My interpretation: the net is learning a new space of representation that is good for describing a metric on the hypersphere. This is a sort of implicit manifold learning. Optimizing by shuffling the assignment is probably crucial since a bad match would not allow similar images to be mapped close to each other in the new representation. Moreover, the network must act as an information bottleneck, as usual. Otherwise, in the limit of infinite capacity the model would simply learn an uninformative 1-to-1 image to noise map. (Thank to Mevlana for stressing this point.)

The promising results from this seriously counterintuitive idea – I mean, the authors wanted to convey so, see the title – is basically reiterating the argument that you should not need labels to find out about patterns in your data, even when the objective is building complex visual features.

See also [Bojanowski et al. arXiv17].

Discovering causal signals in images [Lopez-Paz et al. CVPR17] I found out about the next from a provocative and inspiring talk by Léon Bottou titled Looking for the missing signal (yes, I stole the title from there). The second half of it is about their WGAN; the relevant bit here is about causality.

But before talking about it, let’s step back for a minute to see how causality may

be relevant for our discussion.

If you learn about causality from a machine learning background, you quickly come to the conclusion that the whole field is missing something rather important at its foundation. We have created a whole industry of methods that learn to associate and to predict things just looking at their correlation in the training data. That won’t do the job in many scenarios. What if we were able to learn models that can take into account causality in their decisions? Basically, can we stop our convolutional network telling us that the animal in the picture is a lion because the background shows the typical Savanna?

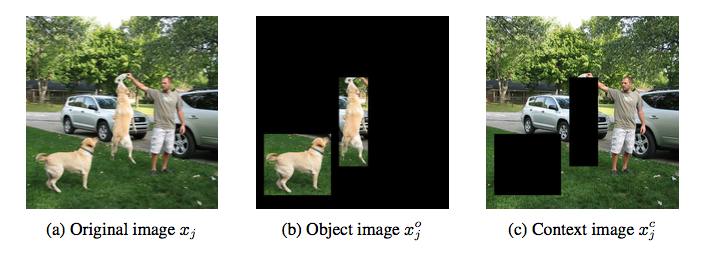

Many are working towards the idea. This paper in particular aims to verify experimentally “that the higher-order statistics of image datasets can inform about causal relations”. More precisely, the authors conjecture that Object features and anticausal features are closely related and vice-versa context features and causal features are not necessarily related. Context features give the background while object features are what it would be usually inside bounding boxes in an image dataset; respectively, the Savanna and the lion’s mane.

Independently, “causal features are those that cause the presence of the object of interest in the image (that is, those features that cause the object’s class label), while anticausal features are those caused by the presence of the object in the image (that is, those features caused by the class label).” Respectively, in our examples a causal feature would be indeed the Savanna’s visual patterns and an anticausal feature would be the lion’s mane.

How did they go about the experiments? My short summary won’t do justice, but I will try. First, we need to train a detector for causal direction. The idea is based on much previous work that demonstrated that “additive causal model” may leave a statistical footprint in observational data about the direction of causality, which in turn can be detected by studying high order moments. (If this sounds all new, I recommend to go through the references of the paper.) The idea is to learn how to capture this statistical trace by a neural network, which is tasked to distinguish between causal/anticausal, i.e. to perform binary classification.

The only feasible way to train such network is by having ground truth label about causality. Not many of those datasets are around. But, the fact is, such data can be easily synthetized, by sampling causes-effect pair of variables and a labels indicating the direction. No image data is used so far.

Second, two version of the images, with either object or context blanked-out, are featurized by a standard deep residual network. Some object and context scores are designed on top of those features as signal to whether the image is likely to be either about an object or its context.

We can now associate object and context with their causal or anticausal role in the image. It results that, for example, “the features with the highest anticausal score exhibit a higher object score than the features with the highest causal score.”

By proving experimentally the conjecture, this work implies that causality in images is in fact related to the difference between objects and their contexts. The result has the promise of opening new research avenues, as better algorithms for causal direction should, in principle, help learning features that generalize better when the data distribution changes. Causality should help with building more robust features by awareness of the generating process of the data.

See also [Peters et al. JRSS15], [Louizos et al. NIPS17].

Reinforcement learning with unsupervised auxiliary tasks [Jaderberg et al. ICLR17] This paper may

be considered a bit old by current standards since it has already 60 citations at

the time I am writing — it was on the arXiv from November `16!

There is in fact some newer work that already builds on the idea. But in fact

I have picked it exactly because of its fundamentally novel insight, instead of discussing

more sophisticated methods based on it.

The scenario is reinforcement learning. A major difficulty in training an agent with reinforcement learning is the sparsity/delay of the rewards. So why not augmenting the training signal by introducing auxiliary tasks? Of course the catch is that the pseudo-reward must be both related to the real objective and engineered without resorting to human supervision.

The proposal of the paper is straightforward and practical: augment the objective function (the reward to maximize) with a sum of performance over auxiliary tasks. The policy has to be learned to do well in the sense of this overall performance. In practice, there are going to be models approximating both the main policy and other policies for accomplishing the additional tasks; those model shares some of their parameters, e.g. the bottom layers can be learned jointly to model raw visual features. “The agent must balance improving its performance with respect to the global reward with improving performance on the auxiliary tasks.”

The kind of auxiliary tasks explored in the paper are the following. First, pixel control. The agent learns a separate policy to maximally change the pixels grids over the input image. The rationale is that “changes in the perceptual stream often correspond to important events in an environment”, hence learning to control changes should be beneficial. Second, feature control. The agent is trained to predict the activation values of hidden units in some intermediate layers of the policy/value network. This idea is interesting “since the policy or value networks of an agent learn to extract task-relevant high-level features of the environment”. Third, reward prediction. The agent learns to predict immediate future rewards. The three auxiliary tasks are learned via experience replay from a buffer of previous experience of the agent.

Cutting short on other details, the whole method is called UNREAL. It is shown to learn faster and better policies on Atari games and Labyrint.

A final insight in the paper is on the effectiveness of doing pixel control instead of simply predicting pixels with a reconstruction loss or the pixel input changes. They can all be seen as form of visual self-supervision, but at different level of abstraction. “Learning to reconstruct only led to faster initial learning and actually made the final scores worse. Our hypothesis is that input reconstruction hurts final performance because it puts too much focus on reconstructing irrelevant parts of the visual input instead of visual cues for rewards”.

![]()

Intrinsic motivation and automatic curricula via asymmetric self-play [Sukhbaatar et al. arXiv17]

The last paper I want to highlight is

related to the idea above of auxiliary tasks in reinforcement learning. But,

crucially, instead of tweaking the objective function explicitly, the agent is

trained to accomplish complete self-plays, simpler tasks that can be generated

automatically — to certain extent.

An initial phase of self-playing is set up by splitting the agent into “two separate minds”, Alice and Bob. The authors propose self-playing under the assumption that the environment has to be (nearly) reversible or resettable to the initial state. In this case, Alice executes a task and asks Bob to do the same, by reaching the same observable state of the world where Alice ended up. For example, Alice could move to pick up a key, open a door, turn off the light and the stop in a certain place; Bob must follow the same list of actions and stop at the same place. Finally, you can imagine that the original tasks for this simple environment is to catch a flag in the room with the light on:

Those tasks are devised by Alice to force Bob to learn interacting with the environment. Alice and Bob have their distinct rewards functions. Bob has to minimize the time for completion, while Alice is rewarded when Bob takes more time, while being able to achieve the goal. The interplay between these policies allow them to “automatically construct a curriculum of exploration”. Once again, this is another realization of the idea of self-supervision for feature learning.

They tested the idea on a few environments and on a version of StarCraft without enemies to fight. “The target task is to build Marine units. To do this, an agent must follow a specific sequence of operations: (i) mine minerals with workers; (ii) having accumulated sufficient mineral supply, build a barracks and (iii) once the barracks are complete, train Marine units out of it. Optionally, an agent can train a new worker for faster mining, or build a supply depot to accommodate more units. […] After 200 steps, the agent gets rewarded +1 for each Marine it has built.”

“Since exactly matching the game state is almost impossible, Bob’s success is only based on the global state of the game, which includes the number of units of each type (including buildings), and accumulated mineral resource. So Bob’s objective in self-play is to make as many units and mineral as Alice in shortest possible time”. In this scenario, self-play really helps to speed up learning with REINFORCE and does better at convergence with respect to REINFORCE + a simpler baseline method for policy pre-training:

Notice althought that the plot does not take into account the time spent in pre-training the policy.

See also [Matiisen et al. arXiv17].

On a final note, it isn’t just that just unsupervised learning is hard, but

measuring its performance is even harder… In Yoshua Bengio’s words :

“We don’t know what is a good representation. […] We don’t have a good definition of what is the right

objective function to even measure that a system is doing a good job on unsupervised learning.”

In fact, virtually all work on unsupervised features learning indirectly uses supervised or reinforcement learning for measuring how useful those features can be. This is OK when unsupervised learning is performed precisely with the intent of improving and speeding up training for predictive models or agents. Yet, the story is different when instead we are after a general representation of, say, videos or texts that should generalize to unseen data distributions “of the same kind”, which is broadly the idea of robust features for transfer learning.

Huge thanks for discussions and feedback to Frank Nielsen, Mevlana Gemici, Marcello Carioni, Richard Nock, Hamish Ivey-Law, Wilko Henecka, Zeynep Akata and Veronika Cheplygina.

References

-

[Bojanowski & Joulin ICML17] Piotr Bojanowski and Armand Joulin, Unsupervised learning by predicting the noise, ICML17

-

[Bojanowski et al. arXiv17] Piotr Bojanowski, Armand Joulin, David Lopez-Paz and Arthur Szlam, Optimizing the latent space of generative networks, arXiv17

-

[Jaderberg et al. ICLR17] Max Jaderberg, Volodymyr Mnih, Wojciech Marian Czarnecki, Tom Schaul, Joel Z Leibo, David Silver and Koray Kavukcuoglu, Reinforcement learning with unsupervised auxiliary tasks, ICLR17

-

[Lopez-Paz et al. CVPR17] David Lopez-Paz, Robert Nishihara, Soumith Chintalah, Bernhard Schölkopf and Léon Bottou, Discovering causal signals in images, CVPR17

-

[Louizos et al. NIPS17] Christos Louizos, Uri Shalit, Joris Mooij, David Sontag, Richard Zemel and Max Welling, Causal effect inference with deep latent-variable models, NIPS17

-

[Matiisen et al. arXiv17] Tambet Matiisen, Avital Oliver, Taco Cohen and John Schulman, teacher-student curriculum learning, arXiv17

-

[Sukhbaatar et al. arXiv17] Sainbayar Sukhbaatar, Zeming Lin, Ilya Kostrikov, Gabriel Synnaeve and Arthur Szlam, Intrinsic motivation and automatic curricula via asymmetric self-play, arXiv17

-

[Peters et al. JRSS15] Jonas Peters, Peter Bühlmann and Nicolai Meinshausen, Causal inference using invariant prediction: identification and confidence intervals, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society ‘17